By Mariam Fam, Deepti Hajela and Luis Andres Henao | The Associated Press

September 7, 2021

NEW YORK (AP) — A car passed, the driver’s window rolled down and the man spat an epithet at two little girls wearing their hijabs: “Terrorist!”

It was 2001, mere weeks after the twin towers at the World Trade Center fell, and 10-year-old Shahana Hanif and her younger sister were walking to the local mosque from their Brooklyn home.

Unsure, afraid, the girls ran.

As the 20th anniversary of the Sept. 11 terror attacks approaches, Hanif can still recall the shock of the moment, her confusion over how anyone could look at her, a child, and see a threat.

“It’s not a nice, kind word. It means violence, it means dangerous. It is meant to shock whoever … is on the receiving end of it,” she says.

But the incident also spurred a determination to speak out for herself and others that has helped get her to where she is today: a community organizer strongly favored to win a seat on the New York City Council in the upcoming municipal election.

Like Hanif, other young American Muslims have grown up under the shadow of 9/11. Many have faced hostility and surveillance, mistrust and suspicion, questions about their Muslim faith and doubts over their Americanness.

They’ve also found ways forward, ways to fight back against bias, to organize, to craft nuanced personal narratives about their identities. In the process, they’ve built bridges, challenged stereotypes and carved out new spaces for themselves.

There is “this sense of being Muslim as a kind of important identity marker, regardless of your relationship with Islam as a faith,” says Eman Abdelhadi, a sociologist at The University of Chicago who studies Muslim communities. “That’s been one of the main effects in people’s lives … it has shaped the ways the community has developed.”

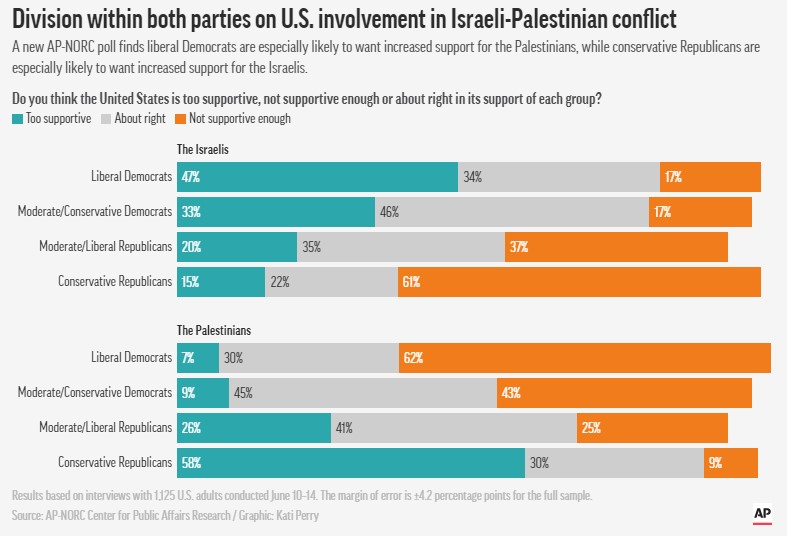

A poll by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research conducted ahead of the 9/11 anniversary found that 53% of Americans have unfavorable views toward Islam, compared with 42% who have favorable ones. This stands in contrast to Americans’ opinions about Christianity and Judaism, for which most respondents expressed favorable views.

Mistrust and suspicion of Muslims didn’t start with 9/11, but the attacks dramatically intensified those animosities.

Accustomed to being ignored or targeted by low-level harassment, the country’s wide-ranging and diverse Muslim communities were foisted into the spotlight, says Youssef Chouhoud, a political scientist at Christopher Newport University in Virginia.

“Your sense of who you were was becoming more formed, not just Muslim but American Muslim,” he says. “What distinguished you as an American Muslim? Could you be fully both, or did you have to choose? There was a lot of grappling with what that meant.”

In Hanif’s case, there was no blueprint to navigate the complexities of that time.

“Fifth-grader me wasn’t naïve or too young to know Muslims are in danger,” she later wrote in an essay about the aftermath of 9/11. “…Flashing an American flag from our first-floor windows didn’t make me more American. Born in Brooklyn didn’t make me more American.”

A young Hanif gathered neighborhood friends, and an older cousin helped them write a letter to then-President George W. Bush asking for protection.

“We knew,” she says, “that we would become like warriors of this community.”

___

But being warriors often carries a price, with wounds that linger.

Ishaq Pathan, 26, recalls the time a boy told him he seemed angry and wondered if he was going to blow up their Connecticut school.

He remembers the helplessness he felt when he was taken aside at an airport for additional questioning upon returning to the United States after a college semester in Morocco.

The agent looked through his belongings, including the laptop where he kept a private journal, and started reading it.

“I remember being like, ‘Hey, do you have to read that?’” Pathan says. The agent “just looks at me like, ‘You know, I can read anything on your computer. I’m entitled to anything here.’ And at that point, I remember having tears in my eyes. I was completely and utterly powerless.”

Pathan couldn’t accept it.

“You go to school with other people of different backgrounds and you realize … what the promise of the United States is,” he says. “And when you see it not living up to that promise, then I think it instills in us a sense of wanting to help and fix that.”

He now works as the San Francisco Bay Area director for the nonprofit Islamic Networks Group, where he hopes to help a younger generation grow confident in their Muslim identity.

Pathan recently chatted with a group of boys about their summer activities. At times, the boys ate watermelon or played on a trampoline. At other moments, the talk turned serious: What would they do if a student pretended to blow himself up while yelling “Allahu akbar,” or “God is great?” What can they do about stereotypical depictions of Muslims on TV?

“I had always viewed 9/11 as probably one of the most pivotal moments of my life and of the lives of Americans across the board,” Pathan says. “The aftermath of it … is what pushed me to do what I do today.”

___

That aftermath has also helped motivate Shukri Olow to do what she is doing — run for office.

Born in Somalia, Olow fled civil war with her family and lived in refugee camps in Kenya for years before coming to the United States when she was 10.

She found home in a vibrant public housing complex in the city of Kent, south of Seattle. There, residents from different countries communicated across language and cultural barriers, borrowing salt from each other or watching one another’s kids. Olow felt she flourished in that environment.

Then 9/11 happened. She recalls feeling confused when a teacher asked her, “What are your people doing?” But she also remembers others who “said that this isn’t our fault… and we need to make sure that you’re safe.”

In a 2017 Pew Research Center survey of U.S. Muslims, nearly half of respondents said they experienced at least one instance of religious discrimination within the year before; yet 49% said someone expressed support for them because of their religion in the previous year.

Overwhelmingly, the study found respondents proud to be both Muslim and American. For some, including Olow, there were occasional identity crises growing up.

“‘Who am I?’ — which I think is what many young people kind of go through in life in general,” she says. “But for those of us who live at the intersection of anti-Blackness and Islamophobia … it was really hard.”

But her experiences from that time also helped form her identity. She is now seeking a seat on the King County Council.

“There are many young people who have multiple identities who have felt that they don’t belong here, that they are not welcomed here,” she says. “I was one of those young people. And so, I try to do what I can to make sure that more of us know that this is our nation, too.”

___

After 9/11, some American Muslims chose to dispel misconceptions about their faith by building personal connections. They shared coffee or broke bread with strangers as they fielded myriad questions — from how Islam views women and Jesus to how to combat extremism.

Mansoor Shams has traveled across the U.S. with a sign that reads: “I’m Muslim and a U.S. Marine, ask anything.” It’s part of the 39-year-old’s efforts to teach others about his faith and counter hate through dialogue.

Shams, who served in the Marines from 2000 to 2004, was called names like “Taliban,” “terrorist” and “Osama bin Laden” by some of his fellow Marines after 9/11.

One of his most memorable interactions, he says, was at Liberty University in Virginia, where he spoke in 2019 to students of the Christian institution. Some, he says, still call him with questions about Islam.

“There’s this mutual love and respect,” he says.

Shams wishes his current work wasn’t needed but feels a responsibility to share a counternarrative he says many Americans don’t know.

Ahmed Ali Akbar, 33, came to a different conclusion.

Shortly after 9/11, some adults in his community arranged for an assembly at his school in Saginaw, Michigan, where he and other students talked about Islam and Muslims. Akbar poured his heart into the research. But he recalls his confusion at some of the questions: Where is bin Laden? What’s the reason behind the attacks?

“How am I supposed to know where Osama bin Laden is? I’m an American kid,” he says.

That period left him feeling like trying to change people’s minds wasn’t always effective, that some were not ready to listen.

Akbar eventually turned his focus toward telling stories about Muslim Americans on his podcast “See Something Say Something.”

“There’s a lot of humor in the Muslim American experience as well,” he says. “It’s not all just sadness and reaction to the violence and…racism and Islamophobia.”

He has also come to believe in building connections of a different type. “Our battle for our civil liberties (is) tied up with other marginalized communities,″ he says, stressing the importance of advocating for them.

___

For some, 9/11 brought a different kind of racial reckoning, says Debbie Almontaser, a Yemeni American educator and activist in New York.

She says many Arab and South Asian immigrants came to the U.S. seeking the American Dream as doctors, lawyers, entrepreneurs. “Then 9/11 happens and they realize that they’re brown and they realize that they’re minorities — that was a huge wake-up call,” Almontaser says.

Some racial tensions play out today in U.S. Muslim communities. The racial justice protests sparked by the killing of George Floyd, for instance, brought many Muslims to the streets to condemn racism. But they also spurred an internal reckoning about racial equity among Muslims, including the treatment of Black Muslims.

“For me, as a Muslim African American, my struggle (in America) is still with race and identity,” says imam Ali Aqeel of the Muslim American Cultural Center in Nashville, Tennessee.

“When we go to (Islamic) centers and we have to deal with the same pain that we deal with out in the world, it’s kind of discouraging to us because we’re under the impression that (in) Islam, you don’t have that racial and ethnic divide.”

___

Amirah Ahmed, 17, was born after the attacks and feels like she was thrust into a struggle not of her making — a burden despite being “just as American as anyone else.”

She recalls how a few years ago at her Virginia school’s 9/11 commemoration, she felt students’ stares at her and her hijab so intensely that she wanted to skip the next year’s event.

When her mother dismissed the idea, she instead wore her Americanness as a shield, donning an American flag headscarf to address her classmates from a podium.

Ahmed spoke about honoring the lives of those who died in America on 9/11 — but also of Iraqis who died in the war launched in 2003. She recalls defending her Arab and Muslim identities that day while displaying her American one and says it was a “really powerful moment.”

But she hopes her future children don’t feel the need to prove they belong.

“Our kids are going to be (here) well after the 9/11 era,” she says. “They should not have to continue fighting for their identity.”

___

Fam, who reported from Cairo, Egypt, covers Islam for the AP’s global religion team. Henao covers faith & youth for the team; he is on Twitter at http://twitter.com/LuisAndresHenao . Hajela has covered New York City for 22 years, and is a member of the AP’s team covering race and ethnicity. She’s on Twitter at http://twitter.com/dhajela . AP video journalist Noreen Nasir also contributed to this report.

___

Associated Press religion coverage receives support from the Lilly Endowment through The Conversation U.S. The AP is solely responsible for this content.