Matt O’Brien | The Associated Press

September 16, 2021

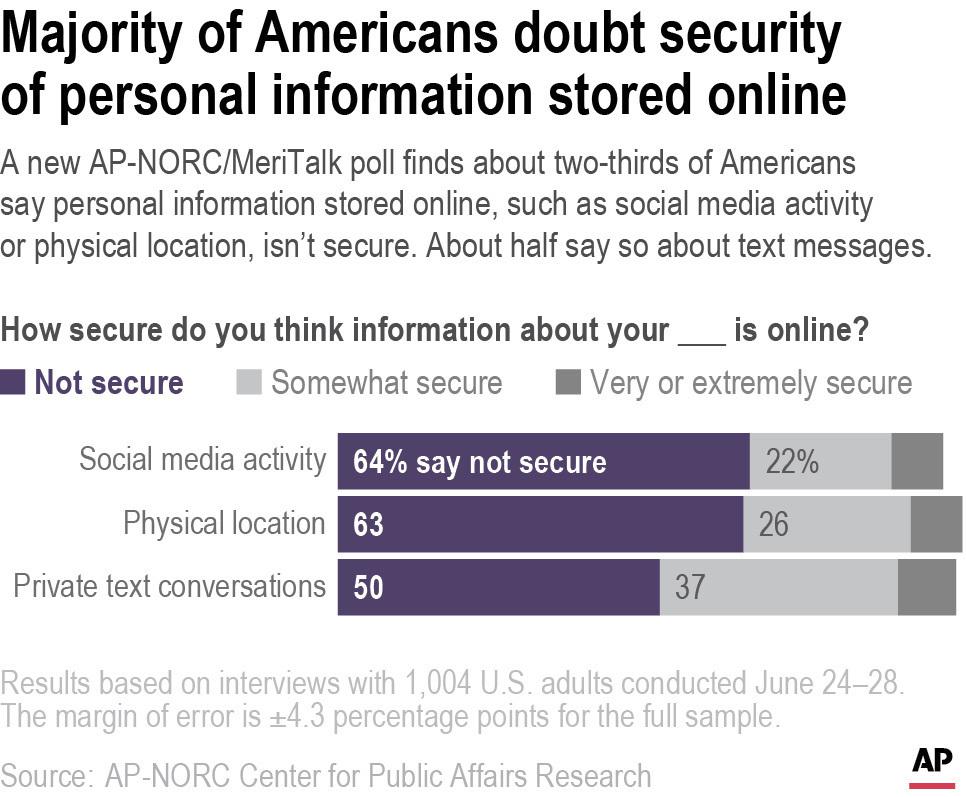

Most Americans don’t believe their personal information is secure online and aren’t satisfied with the federal government’s efforts to protect it, according to a poll.

The poll by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research and MeriTalk shows that 64% of Americans say their social media activity is not very or not at all secure. About as many have the same security doubts about online information revealing their physical location. Half of Americans believe their private text conversations lack security.

And they’re not just concerned. They want something done about it. Nearly three-quarters of Americans say they support establishing national standards for how companies can collect, process and share personal data.

“What is surprising to me is that there is a great deal of support for more government action to protect data privacy,” said Jennifer Benz, deputy director of the AP-NORC Center. “And it’s bipartisan support.”

But after years of stalled efforts toward stricter data privacy laws that could hold big companies accountable for all the personal data they collect and share, the poll also indicates that Americans don’t have much trust in the government to fix it.

A majority, 56%, puts more faith in the private sector than the federal government to handle security and privacy improvements, despite years of highly publicized privacy scandals and hacks of U.S. corporations from Target to Equifax that exposed the personal information of millions of people around the world.

Indeed, companies such as Apple have made a big push to pitch themselves as attuned to consumer privacy preferences and committed to protect them.

“I feel there is little to no security whatsoever,” said Sarah Blick, a professor of medieval art history at Kenyon College in Ohio. The college’s human resources department told Blick earlier this year that someone fraudulently applied for unemployment insurance benefits in her name.

Such fraud has spiked since the pandemic as perpetrators buy stolen personal identifying information on the dark web and use it to flood state unemployment systems with bogus claims.

“I believe my information was stolen when one of the credit bureaus was hacked, but it also could have been when Target was hacked or any other of the several successful hacks into major corporations,” Blick said.

About 71% of Americans believe that individuals’ data privacy should be treated as a national security issue, with a similar level of support among Democrats and Republicans. But only 23% are very or somewhat satisfied in the federal government’s current efforts to protect Americans’ privacy and secure their personal data online.

“This is not a partisan issue,” said Colorado state Rep. Terri Carver, a Republican who co-sponsored a consumer data privacy bill signed into law by Democratic Gov. Jared Polis in July. It takes effect in 2023.

The legislation, which met opposition from Facebook and other companies, follows similar measures enacted in California and Virginia that give people the right to access and delete personal information. Colorado’s also enables people to opt out of having their data tracked, profiled and sold.

“That was certainly one of the pieces where we got the strongest pushback but we felt it was so important,” Carver said. “There’s great frustration that individuals have that they don’t have the tools and the legal support to establish any kind of effective control over their personal data.”

Carver said it took several years to get the law passed, and advocates had to abandon some priorities, such as the idea of enabling people to opt in if they want to allow processing of their personal data — instead of making them opt out. She hopes the efforts by Colorado and other states push Congress to set nationwide protections.

“We need a strong federal data privacy bill,” she said. “It would just make sense, given interstate commerce.”

The poll also found broad agreement in how Americans look at technology: 81% of Democrats and 78% of Republicans say they view technology as playing a major role in the country’s ability to compete globally. Seventy-nine percent of Democrats and 56% of Republicans see value in the government’s technology investments.

At least 6 in 10 adults support the federal government taking measures such as spending more on technology, expanding access to broadband internet and strengthening copyright protections to improve U.S. competitiveness.

There are some generational variations in support for government policies to safeguard data privacy and security, though majorities across age groups are in favor. While 85% of adults age 40 and older are in favor of stronger punishments for cyber criminals, 70% of younger adults say the same.

“The underlying current is that this is an area where people do see a direct role in government,” Benz said. “This is something pretty tangible for people.”

____

The AP-NORC poll of 1,004 adults was conducted June 24-28 using a sample drawn from NORC’s probability-based AmeriSpeak Panel, which is designed to be representative of the U.S. population. The margin of sampling error for all respondents is plus or minus 4.3 percentage points.