With Americans’ disapproval of Congress reaching record levels in recent years, the strength of the country’s legislative system and America’s faith in its outcomes have come into question. This study reveals a new explanation for Americans’ dissatisfaction with their elected representatives by showing that people’s approval of Congress is tied to their beliefs about how lawmakers are making decisions.

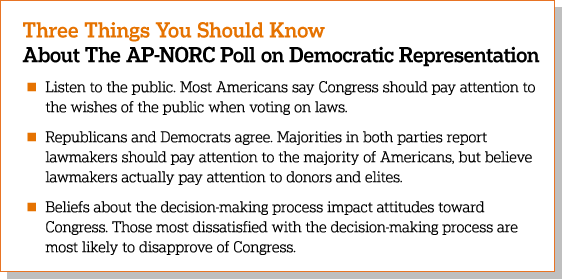

The study—conducted through a collaboration of researchers from Stanford University, the University of California, Santa Barbara, and The AP-NORC Center—shows that negative attitudes toward Congress relate to the gap between what people think members of Congress should pay attention to when voting on a law and what people think they do pay attention to when voting. The phenomenon cuts across partisan lines, and these perceptions of the decision-making process affect both Democrats’ and Republicans’ approval of Congress.

The public’s assessment of Congress’s decision-making process, calculated as the difference between who Americans want Congress to pay attention to and who they think Congress actually is paying attention to, is a new explanation for the current low levels of approval of Congress. Many past studies have focused on how the number of laws passed by Congress and legislative outcomes impact Americans’ attitudes toward their representatives. This research accounts for these factors of “volume disapproval” and “outcome disapproval,” and additionally reveals that opinions of Congress also depend on this idea of “decision-making process disapproval”: who people think Congress is paying attention to when making laws, and who they are not.

The results show that Americans’ negative views of Congress are related to their belief that representatives are listening to the wrong people and groups. More than 9 in 10 of those with the largest overall difference in opinions between how representatives should decide and how they actually decide disapproved of Congress, compared to 7 in 10 people with the smallest overall difference. Additionally, those with the highest disapproval of Congress’s decision-making process are more likely to rate Congress as doing a poor or very poor job (84 percent), compared to those with the lowest levels of process disapproval (36 percent).

Democrats and Republicans are largely united on this issue. Both Democrats and Republicans report that Congress should pay a lot of attention to the public but believe representatives instead listen to elites and donors. Americans who identify as Democrats and those who identify as Republicans are both more likely to disapprove of Congress overall and see government as not working well the more they are dissatisfied with Congress’s decision-making process.

The findings indicate a possible path out of the current rut of Congressional disapproval. The data clearly reveal that most people want their representatives to pay more attention to the views of the public. To do this, members of Congress need to know what those views are. While they do hear from interested publics who write letters and participate in the political process, Congressional representatives do not have a clear way to understand the views of their general constituency, which often do not align with the views of those publics especially engaged in an issue. High-quality public opinion polling at the state level is rare, and it is virtually non-existent at the level of Congressional districts. Furthermore, what polling does occur is often focused on electoral politics and not policy issues. Beyond the need for better measurement of public opinion on key legislative issues facing representatives, the findings also suggest that it would be beneficial for Congress, as an institution, to be more transparent in its decision-making process and make clear to the public how different groups—from the public to donors—are contributing to voting decisions.

The results are based on a nationally representative online survey of 1,021 Americans conducted from September 17 to October 19, 2015, using AmeriSpeak®, the probability-based panel of NORC at the University of Chicago. The study was funded by the Woods Institute for the Environment at Stanford University and by NORC. The study was replicated with a second survey in 2017 that confirmed the initial findings. The 2017 survey was conducted with 355 Americans using the AmeriSpeak Panel between August 29 and September 8.